When I first started researching my family history, I soon realized that until recently, women and children were at the mercy of the survival and success of the men in their lives. This realization has made me appreciate my ability to earn a living. I find it difficult not to empathize with the struggles of the people I study. Sometimes, I continue as a personal project, hoping to find a happy ending. Most subjects are women, and I call them “my ladies.”

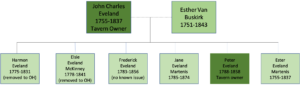

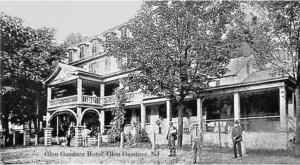

Julia Beam was not one of my ancestors and had no connection to my family. I “met” her while researching the sleepy town of Glen Gardner, New Jersey, in connection with Hunterdon County’s 300th anniversary. She was hard to miss; her story jumped off the old newspapers, creating a stir. I had to finish my work on what was then the Glen Gardner Inn (originally Eveland’s Tavern), so she did get put aside for a bit. Part of her tale had events at the Inn, so she kept popping in and out of that project. Several years have passed, and I have finally found the “rest of her story.”

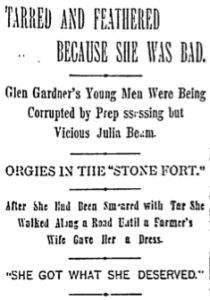

The first news article I came across had attention-grabbing quotes and painted a picture of a woman who deserved to be punished:

The article mentioned that Julia fell in with Melville Walters, a shiftless fellow. When he brought her to Glen Gardner, he claimed Julia was his wife. The article disputed the marriage since Walters was already married and was not yet divorced.

After the attack, Julia fainted and woke right after dawn. She had no clothing and was tar-covered. Julia attempted to seek help from her husband at his parent’s house, but he turned her away. She then headed to her parents’ home 6 miles away in Califon. Along the way, a farmer’s wife gave her a dress to cover herself.

What struck me was the tarring and feathering; wasn’t that something that had died out well before 1891? It also appeared as if the town residents seemed proud that they had done this to a nineteen-year-old woman. John Banghart, who led the attacking party, had announced his intentions to a group of people, including two of the town’s “leaders,” Dr. Hunt and Miller Crawley, who offered to supply the tar.

As a genealogist, I try not to judge the past by modern standards, but this shocked me. Were times so different that an entire town thought it was ok to hurt a young woman in this manner? The following article I stumbled upon, “Those Heroic White Caps,” answered my question. The “White Caps,” or “Regulators,” had the community’s “moral support”:

They claimed to have the moral support of the entire neighborhood, and the local Justice of the Peace took no action in the premises.

Sheriff Lake appeared on November 13 with eleven warrants for the arrest of the “regulators.”[ii]

A bunch of men dressed as women, or with their faces covered, decided to injure and run a young woman out of town because they felt she led their sons astray. “Not my child” is not a new parental phenomenon.

I also wanted to know what a white cap was in 1891. Were they the Ku Klux Klan? In a tiny town in New Jersey? The white cap definition was difficult to find, but white capping is referred to in a few law books, but those laws focused on violence against minority groups. Julia Beam was not a minority; the definition found in Wikipedia most accurately fits this case:

Whitecapping was a violent lawless movement among farmers that occurred specifically in the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It was originally a ritualized form of enforcing community standards, appropriate behavior and traditional rights.[iii]

My conclusion is that it was a term the newspapers used for vigilantism; it may be intertwined with white supremacist groups, but race was not a factor in this event. Julia became one of my ladies when I read the first headline. She physically survived her ordeal, but I wondered if she went on to live an everyday life. The following post will examine Julia’s life before and after the attack.

Continue to part two, the early life of Julia Beam

Sources:

[i] “Tarred and Feathered because she was bad,” The New York Herald [New York], 8 November 1891, page 18, column 1, digital image; Genealogybank.com (http:// www.genealogybank.com : accessed 21 October 2017).

[ii] “Those Heroic White Caps,” The New York Herald [New York], 20 November 1891, page 11, column 4, digital image; Genealogybank.com (http:// www.genealogybank.com : accessed 21 October 2017).

[iii] “Whitecapping,” Wikipedia (http:// https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitecapping : accessed 21 January 2018).